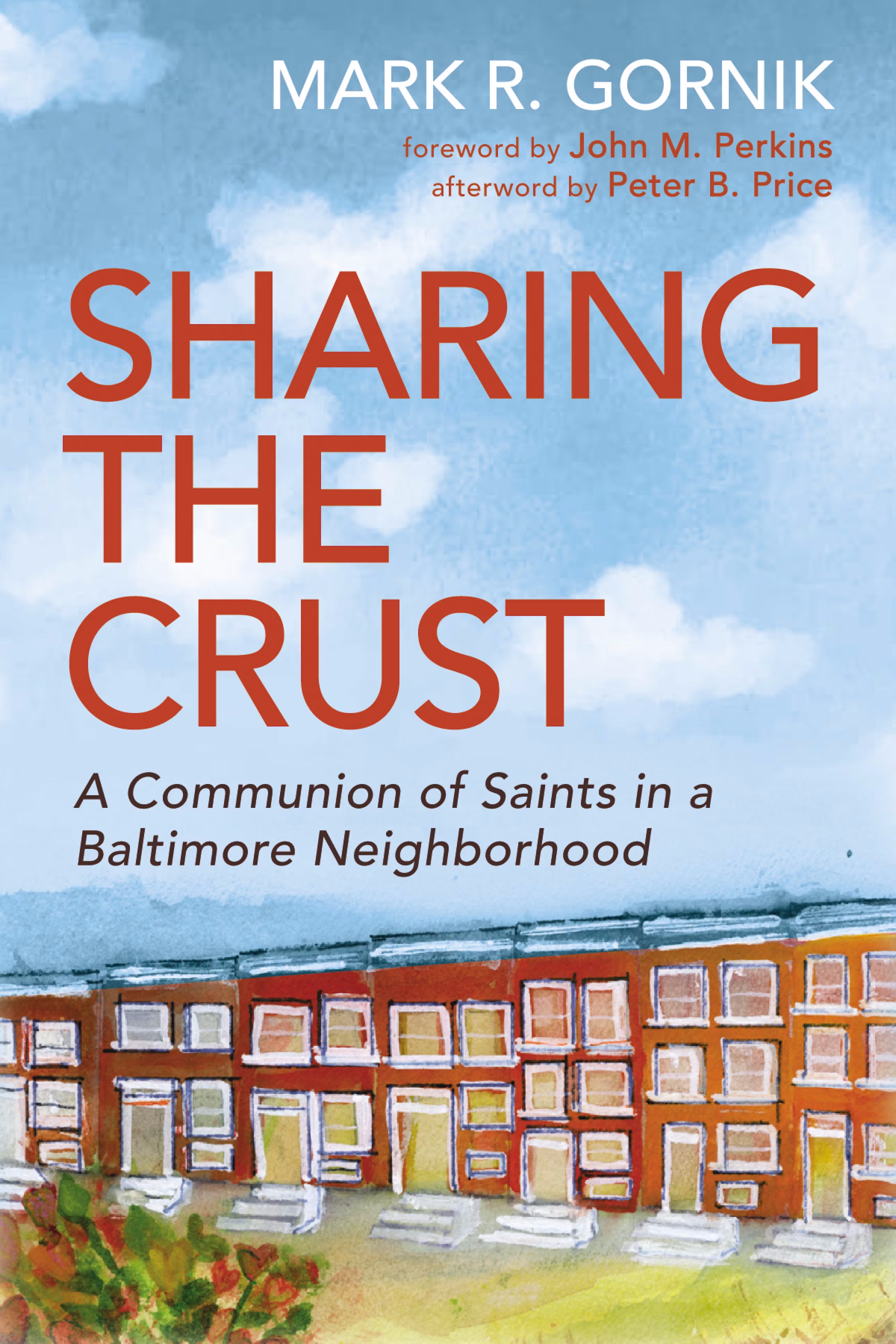

Last week I attended a book launch event at my work place. Mark, the director of the seminary, was sharing about his recently published book, Sharing the Crust, a story about friendship and a community of saints that developed in Sandtown, Baltimore.

The book offers snapshots of communal life in Sandtown and on relationships between members of the community. There was so much love and affection between the members of Sandtown as I read the story, sat on the stoop with the community, joined the volunteers in restoring abandoned homes, listened to journal entries and reflections.

During the book launch event, Mark shared anecdotes and context around the book. There was a conversation around why he wrote the book and what he hoped his readers to learn. At the end there was a Q&A session and it seemed that most people were really inspired and interested in how to do this kind of work — good work to build community that would transform lives and generations; we certainly need more good news and good efforts. But I was personally drawn to a comment Mark made closer to the end of his sharing when he shared about how the neighborhood regressed.

It was the regression, the sense of loss, the felt guilt/grief that I connected with the most. In a passing comment, Mark mentioned that he still wakes up every morning thinking of himself as a pastor in Sandtown; he wakes up and thinks about the people of Sandtown and the people of the Seminary. As much as I feel like I’ve processed my grief and “moved on,” the reality is that I still think about my former church on a daily basis. Every morning when I leave the house, a thought about a former congregant or how I imagine the church responding to current events still crosses my mind. I don’t try to think about it; the thoughts come unbidden. And while it no longer pains me to the same degree as when my parting was fresh, the outlines of grief are still there.

I’m sure in a decade or so when the children of my former congregants are already in the workforce, there will still be mornings where I wake up and think about a family whose child has already grown up. There will be mornings when I think about how the church is approaching racism and inclusion (the heightened sense of purpose from the last years of my pastoral work there from 2020-2022) before church pressures forced me out. There’s still much that I mourn even now.

In my own reflections about my pastoral journey, I often try to reason with myself that all is not lost. And I know that’s true even though I sometimes feel differently. I can’t remember where it was in the book, but there was a line (somewhere in the first third of the book that I read for a staff discussion) that spoke about how we can never know in the present how the Spirit will stitch all the broken/random/isolated pieces of our stories together in the future (my own reinterpretation of what I remember). But the lines that rang with a heart-resonant tone at the book launch/sharing wasn’t merely “all is not lost,” but “nothing is lost.” All the good that I’ve done in my pastoral work continues and will last to the end. Am I a pastor? Maybe to some I still am, but most of the time it feels like I’m molting that former identity. Perhaps one day, this lingering identity as “pastor” would re-emerge, but for now I live with this tension of grief and loss, joy and hope, waiting to see how the Spirit’s work unfolds.